Photos: Josh Caffrey

Blackburn recently sat down with brand ambassador Erick Cedeño following his successful retracing of the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps route from Missoula, MT to St. Louis, MO. The trip had been a dream of his for years, and the finish in St. Louis garnered national attention and moved Cedeño to tears. The mayor of St. Louis decried that July 24th shall now be known as “Iron Riders Day.”

For a man who set out to shine light on the African American soldiers of the 25th, the end of the ride could not have been more fitting.

Erick Cedeño was a long-time bicycle traveler before he ever created “Bicycle Nomad.” During one of his early longer trips he realized that by combining his rides with his interest in history he could stay motivated. We centered this interview on some of his origin story, but focused more on the details of his 25th Infantry “Buffalo Soldier” route.

WHAT MOTIVATES YOU DO TO HISTORICAL RIDES?

I found out that it was hard for me to always stay motivated on longer rides. I needed a carrot … when I did a trip from Miami to New York City, I literally traveled through sections of history. I learned about parts of the Civil War in South Carolina. I went through Jamestown in Virginia, and went into D.C. And I’m like: “Man, maybe I should combine my love of history and my love for traveling by bike together, to use it as a carrot to help me go to the next town.”

On my next trip after that, I wanted to do [the] Lewis and Clark Expedition. As I did some research on that route, I started learning more about the Underground Railroad And I thought: “Oh, I wonder if I could travel through routes of the Underground Railroad.” And there were so many routes of the Underground Railroad. So I just started doing research and see what I could do, and I came across … Adventure Cycling, they had an Underground Railroad route that followed an old spiritual song called “Follow the Drinking Gourd.”

“Follow the Drinking Gourd,” people used to sing it [on] plantations, but it was actually a GPS to tell people how to travel to freedom, north into Canada. What (the lyrics) say was to follow the Tennessee River into the Ohio River, and follow the Big Dipper. That’s pretty much the whole song.

I thought: “Oh, man. Follow the Drinking Gourd. I should do that.” And that’s how I did it. And I loved it. I love traveling through history because, like I mentioned, I learn something in one town, and I can’t wait till I get to the next place so I could see more.

And then I rode into Cincinnati, which has the National Underground Railroad Museum, which is an amazing museum. I spent two days looking at the history of the Underground Railroad. And it’s part of my route. So yeah, now that’s all I want to do: I want to travel by bicycle and through history. I really enjoy it.

WHEN YOU FIRST BEGAN WORKING WITH BLACKBURN, YOU HAD DONE THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD ONCE. YOU WERE ABOUT TO DO IT AGAIN. IN PROBABLY THE VERY FIRST CONVERSATION THAT WE HAD, YOU MENTIONED THE 25TH INFANTRY BICYCLE CORPS. IT WAS KIND OF ALREADY ON YOUR BUCKET LIST, OR IT WAS ALREADY IN YOUR SIGHTS DOWN THE ROAD. RIGHT? HOW DID YOU FIRST HEAR ABOUT THEM?

At some point on my first really long trip from Canada to Mexico, I wonderd: “Who were the first people that traveled by bicycle? And why did they do it? And where did they go? I want to see their bikes.” I wanted to know everything about the history of that. I love history, like I mentioned before.

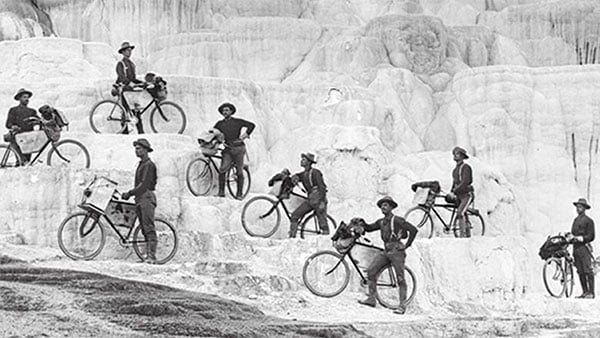

As I started doing some research, I came across several expeditions around the late 1890s, usually one person or two people. And then I came across the 25th Infantry. And I was just fascinated because up to that point I didn’t see anyone, especially black men, traveling by bicycle. And I was wondering if it has been done before and but wasn’t documented. Luckily for us, this expedition of the 25th was documented by the U.S. Army.

When I read about the 25th in Dirt Rag Magazine in about 2011 I was like “One day I will recreate this route.”

AND THE FACT THAT THESE SOLDIERS WERE AFRICAN AMERICAN RESONATED WITH YOU?

Back when I started getting into Instagram in 2015–16, I was inspired by all of these trips that I saw that people were doing, but I didn’t see a representation of a person of color traveling by bike. So for Bicycle Nomad, it was important for me to start to show that, to leave a legacy. Recreating this expedition was important. I want to inspire people to travel by bike, especially people of color.

I want people to look at this ride at think: “Wow, look at this. This was done in 1897 by black soldiers. How come I didn’t learn about this in history class? And if they did it, then I can do it.”

Other projects kept popping up, and it never happened until 2022, which I’m glad that it did because it was the 125th anniversary of the trip.

HOW MUCH OF THE ROUTE WAS KNOWN? HOW MUCH OF IT DID YOU HAVE TO WORK OUT ON YOUR OWN?

Yeah, that took us a long time. And it wasn’t on my own. I worked with historians (Mike Higgins and Arlen Hall) because it was very important for me to stay as close to the accuracy of this route, of this expedition of 1897. I didn’t want to go places that they didn’t go just because it was easier. It took us more than six months to figure out the route.

Mike actually tried to recreate the route, maybe in 2009 I think and failed just because it was very grueling. He got into some snow up in Montana. The good thing about it was that he went to several libraries and historical societies to [be] able to put some of the pieces together that helped me with my project in 2022. We contacted each other several times, and we met each other in Bozeman, Montana just to talk about several other projects that we’re working on.

I’m trying to match up the names of the 20 bicycle riders with images. We only have about seven of them. I was able to work with him on that, and we’re trying to figure out the next 12 people, 13 people that we don’t have. Several of those riders are essentially unknown. Maybe buried without tombstones.

WHEN YOU FOUND OUT, WHEN YOU LEARNED THAT MOST OF THESE SOLDIERS, MOST OF THESE RIDERS, WE DON’T KNOW WHO THEY ARE AND THEY MAY NOT HAVE HAD ANY MARKINGS ON THEIR GRAVES, HOW DID THAT MAKE YOU FEEL?

That’s when I realized I have to do something about this project because I realized … You know what I thought then? I thought: “This is somebody’s grandfather, great-grandfather, somebody’s father that history didn’t recognize for something that was so epic.”

We’re able to know a lot of expeditions, and we know a lot of the history of the U.S. How come we don’t know anything about this man? Because what they did — for me, at least — it was something very epic that we will talk about, people that travel by bicycle, for the rest of our life. And my son will talk about it, and his son will talk about it because it was that epic: that in 1897, a group of soldiers were able to do — black soldiers were able to do what they did.

So that sat in me. That sat in me big time. I teared up when I recognized that these men… You have to understanm-d: For 125 years, no one ever questioned: How come I don’t know people’s names or faces?

WE KNOW TRIPS LIKE THIS HAVE HIGHS AND LOWS. WE KNOW YOU HAD AN OPPORTUNITY TO STAY IN SOME OF THE SAME PLACES THAT THE 25TH STAYED. WOULD YOU CONSIDER THOSE NIGHTS HIGH POINTS?

Oh, yeah. There was a series of them. When I travel through history, especially on the Underground Railroad, I wanted to stay at historical sites. I just don’t want to ride my bike. That’s fun, but I want to experience the people that travel. I call them “freedom seekers.” These freedom seekers, where did they stay?

I want to stay there. Those are highlights. I know the feeling of staying at places people stayed in 1850s, and that they were used as a safeguard to move onto freedom. They’re actually hard to sleep in, those places, because you know that there was — you feel the energy, and you know the history. So for me, it’s usually hard to sleep in those places. But when I recreated the route of the 1897 expedition, I also wanted to stay in places they stayed, where they camped out, and [the forts].

THE BEAUTY OF TRAVELING BY BICYCLE THROUGH HISTORY IS DOING THE RESEARCH. I THINK THAT THAT’S THE BEAUTY OF IT: TO BE ABLE TO READ AND THEN GO BACK. NO ONE HANDED ME A BOOK FOR THIS TRIP AND SAID: ‘THIS IS THE ROUTE, AND THIS IS WHERE THEY STAYED.’ SO WE HAD TO RECREATE THAT, AND WE HAD TO FIGURE IT OUT. AND THEN WHEN YOU’RE OUT THERE, IT JUST TASTES DIFFERENT. IT’S A SWEETER PLACE.— Erick Cedeño

SO YOU’RE OUT THERE FOR 40 DAYS, YOU RIDE ALMOST 2,000 MILES, CLIMB 55,000 FEET ALL DURING SOME OF THE WETTEST WEATHER WE HAD IN THE US THIS SUMMER … AND IT’S HOT. WHAT KEPT YOU MOTIVATED?

I brought a picture of these guys with me. It’s 125 years’ anniversary. It was my responsibility to finish the route, to inspire people. The “Why’s” became very important. But that picture was there, reminding me why I was doing this. It was my responsibility to finish the route, to inspire people. But that picture was always there on top of my handlebar bag.

WE KNOW YOU OFTEN BRING A PICTURE OF A LOVED ONE WITH YOU ON YOUR TRIPS. WHAT ARE SOME OF THE OTHER ESSENTIALS YOU ALWAYS BRING?

For me, hygiene is #1. I like brushing my teeth and washing my face … so yeah shampoo and face wash. When I see peoples lists they never mention hygiene. I want to put that out there, it’s important to take care of yourself.

When I take a historical trip, I like to bring a book about the subject matter I’m riding through. I brought a book about the Bicycle Corps. At night when I go to bed, or when I leave in the morning, it helps me stay connected.

I always bring coffee or tea with me … caffeine helps on a long ride, but it’s also about the ritual. I went very light for this trip, I tried to keep my gear under 30 lbs, so I went with instant coffee. I don’t drink it first thing in the morning. I break down camp and get on the road. I don’t stop for coffee until 10–11 am.

In the past I didn’t put on a Hitchhiker, but on this trip I did. And it was so awesome because it was where I kept my easy-to-grab stuff. I could actually ride my bike and reach over and get a ChapStick or ear pods without stopping.

WE NOTICED YOU HAD A PATCH ON YOUR HITCHHIKER FOR THIS RIDE. WHAT IS THAT PATCH?

Yeah. So this year, I was inducted to The Explorers Club, which is one of my top honors. And I don’t know how to say it, but lifetime milestone, I would say for me, is to be a part of such a prestigious organization you know, and I would say marrying my wife, my son, graduating from college. That is in the top five: to be a part of that organization.

I don’t know if there’s another bike packer in that organization. But to finally open the door to let people know that this is an exploration, too. Yeah, you could go up to the space and you could go down to the bottom of the ocean, but we explore by bike. And that’s one of the reasons, I think, that they started opening up.

The new president decided he wanted to have diversity in The Explorers Club. Not only race and not only age, but also the way people explore. He knew that that was important: the other ways to explore the earth. And for me to be a part of that is an honor. So I wanted to carry the flag of The Explorers Club, and I was able to put that patch on my Hitchhiker. Yeah, it will always be there.

WHAT IS THE BIGGEST TAKE AWAY YOU HAVE FROM THIS TRIP?

I’m not sure if it’s metaphysics or what, but I was talking to my father on the phone right before the trip and he said to me “Wow, imagine if all of this information landed with you because you were chosen to tell this story?” And that made me tear up, I felt this pressure. But my wife encouraged me, saying “Who else can tell this story?” because she knew I could put in the miles, and do the research and get it in front of people because I’m obsessed with telling this story.